FAQ

Colon Cancer Screening Saves Lives

Approximately 150,000 new cases of colorectal cancer are diagnosed every year in the United States and nearly 50,000 people die from the disease. It has been estimated that increased awareness and screening would save at least 30,000 lives each year. Colorectal cancer is highly preventable and can be detected by testing even before there are symptoms. The American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy encourages everyone over 50, or those under 50 with a family history or other risk factors, to be screened for colorectal cancer.

A colonoscopy screening exam is almost always done on an outpatient basis. The procedure typically takes less than 45 minutes.

Six Questions That Could Save Your Life

(or the Life of Someone You Love)

Test your knowledge about colorectal cancer (CRC) screening. If you think the answer is true or mostly true, answer true. If you think the answer is false or mostly false, answer false.

1. Colorectal cancer is predominantly a “man’s disease,” affecting many more men than women annually.

FALSE. Colorectal cancer affects an equal number of men and women. Many women, however, think of CRC as a disease only affecting men and might be unaware of important information about screening and preventing colorectal cancer that could save their lives, says the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy.

2. Only women over the age of 50 who are currently experiencing some symptoms or problems should be screened for colorectal cancer or polyps.

FALSE. Beginning at age 50, all men and women should be screened for colorectal cancer EVEN IF THEY ARE EXPERIENCING NO PROBLEMS OR SYMPTOMS.

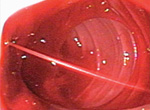

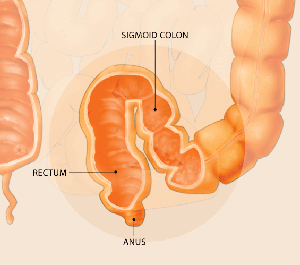

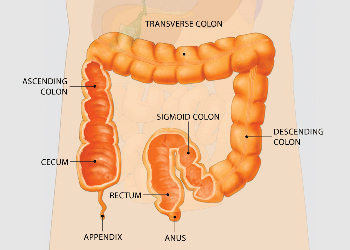

In a colonoscopy, the physician passes the endoscope through your rectum and into the colon, allowing the physician to examine the tissue of the colon wall for abnormalities such as polyps.

3. A colonoscopy screening exam typically requires an overnight stay in a hospital.

FALSE. A colonoscopy screening exam is almost always done on an outpatient basis. A mild sedative is usually given before the procedure and then a flexible, slender tube is inserted into the rectum to look inside the colon. The test is safe and the procedure itself typically takes less than 45 minutes.

4. Colorectal cancer is the third leading cause of cancer deaths in the United States.

TRUE. After lung cancer, colorectal cancer is the third leading cause of cancer deaths in the United States. Annually, approximately 150,000 new cases of colorectal cancer are diagnosed in the United States and 50,000 people die from the disease. It has been estimated that increased awareness and screening would save at least 30,000 lives each year.

5. Tests used for screening for colon cancer include digital rectal exam, stool blood test, flexible sigmoidoscopy and colonoscopy.

TRUE. These tests are used to screen for colorectal cancer even before there are symptoms. Talk to your healthcare provider about which test is best for you. Current recommended screening options* include:

Beginning at age 50, men and women should have:

- An annual occult blood test on spontaneously passed stool (at a minimum);

- A flexible sigmoidoscopy every 5 years; or,

- A complete colonoscopy every 10 years.

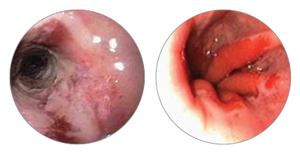

The endoscope is a thin, flexible tube with a camera and a light on the end of it. During the procedure, images of the colon wall are simultaneously viewed on a monitor.

Important: You may need to begin periodic screening colonoscopy earlier than age 50 years if you have a personal or family history of colorectal cancer, polyps or long-standing ulcerative colitis.

6. Colon cancer is often preventable.

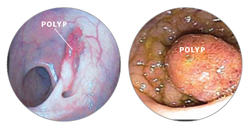

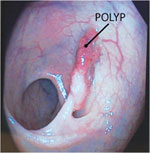

TRUE. Colorectal cancer is highly preventable. Colonoscopy may detect polyps (small growths on the lining of the colon). Removal of these polyps (by biopsy or snare polypectomy) results in a major reduction in the likelihood of developing colorectal cancer in the future.

For Your Information

The American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy encourages you to talk with your healthcare provider about colon cancer screening and encourages everyone over the age of 50 to undergo the appropriate screening. If your primary healthcare provider has recommended a colonoscopy, you can find a physician with specialized training in these GI endoscopic procedures by using the free Find a Doctor tool on ASGE’s Web site at www.screen4coloncancer.org. For more information about colon cancer screening, visit www.screen4coloncancer.org.

Why Should You Choose an ASGE Member for Your Endoscopic Procedure?

Having an ASGE member perform your endoscopic procedures ensures that you are in the hands of someone who is highly trained. Physicians and surgeons who are members of the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE) have highly specialized training in endoscopic procedures of the digestive tract, including upper GI (gastrointestinal) endoscopy, flexible sigmoidoscopy, colonoscopy, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) and endoscopic ultrasound (EUS).

ASGE members undergo a rigorous application and screening process and are recognized by the medical community as knowledgeable, experienced experts in gastroenterology and GI surgery who, in addition, have advanced training in gastrointestinal endoscopic procedures.

ASGE members have demonstrated proof of rigorous endoscopic training. The American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy is the only medical society that requires documentation of specific training in GI endoscopic procedures.

How will your GI endoscopist work with your primary care physician?

ASGE physicians usually work on referral from your primary care physician. Your GI endoscopist will communicate with your primary care physician about the results of your endoscopic procedure. Together, they will determine what is appropriate for treatment, follow-up visits and/or if future endoscopic exams are needed.

Is your physician an ASGE member? Ask.

Make the best choice. If you need an endoscopic procedure, ask your primary care doctor to recommend a specialist in gastrointestinal endoscopy who is also an ASGE member. ASGE members are distinctively qualified to perform the gastrointestinal endoscopic procedures that your primary care physician or other healthcare provider recommends and to work with you and your primary care provider on issues of digestive health.

Find an endoscopist in your area.

ASGE can help you find a GI endoscopist in your area. It’s easy. Visit the ASGE Web site at www.asge.org and click on the Find an Doctor. By typing in your zip code, the Find a Doctor program will give you a list of the ASGE members in your area. Remember, you can always ask if your physician is an ASGE member.

Need more information on endoscopy or colonoscopy?

ASGE offers additional materials on GI endoscopy and endoscopic procedures including brochures on Upper GI Endoscopy, Endoscopic Ultrasound, ERCP, Flexible Sigmoidoscopy and Colonoscopy on the ASGE Web site at www.asge.org as well as other useful information on digestive health and gastrointestinal problems.

Make the Best Choice for Your Endoscopic Procedure-An ASGE Gastrointestinal Endoscopist

ASGE Active Physician Members have met the following rigorous requirements:

- Unlimited medical license.

- Graduation from an accredited medical school and completion of a residency program.

- Documented evidence of formal training in gastrointestinal endoscopy under the supervision of certified gastroenterologists or gastrointestinal surgeons – ASGE is the only society that requires evidence of such training.

- Finally, ASGE Active Members must provide evidence of professional competence through sponsorship by at least one member who has personal knowledge of the applicant’s endoscopic training and skills.

Be certain your physician meets the high standards of ASGE membership.

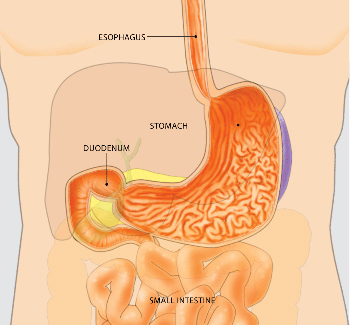

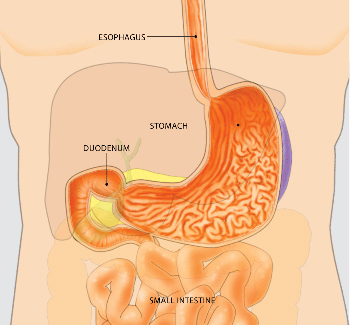

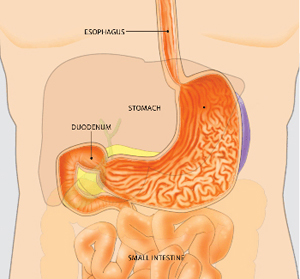

What is upper endoscopy?

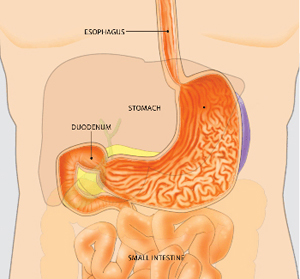

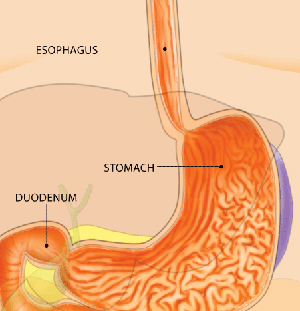

Upper endoscopy lets your doctor examine the lining of the upper part of your gastrointestinal tract, which includes the esophagus, stomach and duodenum (the first portion of the small intestine). Your doctor will use a thin, flexible tube called an endoscope, which has its own lens and light source, and will view the images on a video monitor.

Why is upper endoscopy done?

Upper endoscopy helps your doctor evaluate symptoms of upper abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting or difficulty swallowing. It’s the best test for finding the cause of bleeding from the upper gastrointestinal tract. It is also more accurate than X-ray films for detecting inflammation, ulcers and tumors of the esophagus, stomach and duodenum. Your doctor might use upper endoscopy to obtain a biopsy (small tissue samples). A biopsy helps your doctor distinguish between benign (non-cancerous) and malignant (cancerous) tissues. Remember, biopsies are taken for many reasons, and your doctor may take a biopsy even if he or she does not suspect cancer. For example, your doctor might use a biopsy to test for Helicobacter pylori, the bacterium that causes ulcers. Your doctor might also use upper endoscopy to perform a cytology test, where he or she will introduce a small brush to collect cells for analysis. Upper endoscopy is also used to treat conditions of the upper gastrointestinal tract. Your doctor can pass instruments through the endoscope to directly treat many abnormalities – this will cause you little or no discomfort. For example, your doctor might stretch (dilate) a narrowed area, remove polyps (usually benign growths) or treat bleeding.

What preparations are required?

An empty stomach allows for the best and safest examination, so you should have nothing to eat or drink, including water, for approximately six hours before the examination. Your doctor will tell you when you should start fasting as the timing

can vary. Tell your doctor in advance about any medications you take; you might need to adjust your usual dose for the examination. Discuss any allergies to medications as well as medical conditions, such as heart or lung disease.

Can I take my current medications?

Most medications can be continued as usual, but some medications can interfere with the preparation or the examination. Inform your doctor about medications you’re taking, particularly aspirin products or antiplatelet agents, arthritis medications, anticoagulants (blood thinners such as warfarin or heparin), clopidogrel, insulin or iron products. Also, be sure to mention any allergies you have to medications.

What happens during upper endoscopy?

Your doctor might start by spraying your throat with a local anesthetic or by giving you a sedative to help you relax. You’ll then lie on your side, and your doctor will pass the endoscope through your mouth and into the esophagus, stomach and duodenum. The endoscope doesn’t interfere with your breathing. Most patients consider the test only slightly uncomfortable, and many patients fall asleep during the procedure.

What happens after upper endoscopy?

You will be monitored until most of the effects of the medication have worn off. Your throat might be a little sore, and you might feel bloated because of the air introduced into your stomach during the test. You will be able to eat after you leave unless your doctor instructs you otherwise. Your physician will explain the results of the examination to you, although you’ll probably have to wait for the results of any biopsies performed.

If you have been given sedatives during the procedure, someone must drive you home and stay with you. Even if you feel alert after the procedure, your judgment and reflexes could be impaired for the rest of the day.

What are the possible complications of upper endoscopy?

Although complications can occur, they are rare when doctors who are specially trained and experienced in this procedure perform the test. Bleeding can occur at a biopsy site or where a polyp was removed, but it’s usually minimal and rarely requires follow-up. Perforation (a hole or tear in the gastrointestinal tract lining) may require surgery but this is a very uncommon complication. Some patients might have a reaction to the sedatives or complications from heart or lung disease. Although complications after upper endoscopy are very uncommon, it’s important to recognize early signs of possible complications. Contact your doctor immediately if you have a fever after the test or if you notice trouble swallowing or increasing throat, chest or abdominal pain, or bleeding, including black stools. Note that bleeding can occur several days after the procedure.

If you have any concerns about a possible complication, it is always best to contact your doctor right away.

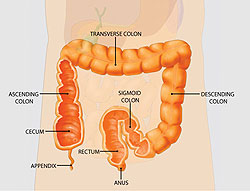

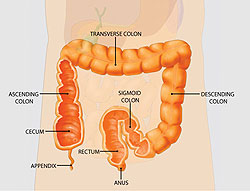

What is a colonoscopy?

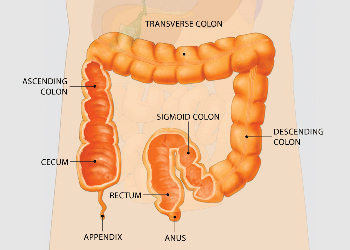

Colonoscopy lets your doctor examine the lining of your large intestine (colon) for abnormalities by inserting a thin flexible tube, as thick as your finger, into your anus and slowly advancing it into the rectum and colon. This instrument, called a colonoscope, has its own lens and light source and it allows your doctor to view images on a video monitor.

Why is colonoscopy recommended?

Colonoscopy may be recommended as a screening test for colorectal cancer. Colorectal cancer is the third leading cause of cancer deaths in the United States. Annually, approximately 150,000 new cases of colorectal cancer are diagnosed in the United States and 50,000 people die from the disease. It has been estimated that increased awareness and screening would save at least 30,000 lives each year. Colonoscopy may also be recommended by your doctor to evaluate for symptoms such as bleeding and chronic diarrhea.

What preparations are required?

Your doctor will tell you what dietary restrictions to follow and what cleansing routine to use. In general, the preparation consists of limiting your diet to clear liquids the day before and consuming either a large volume of a special cleansing solution or special oral laxatives. The colon must be completely clean for the procedure to be accurate and comprehensive, so be sure to follow your doctor’s instructions carefully.

Can I take my current medications?

Most medications can be continued as usual, but some medications can interfere with the preparation or the examination. Inform your doctor about medications you’re taking, particularly aspirin products, arthritis medications, anticoagulants (blood thinners such as warfarin or heparin), clopidogrel, insulin or iron products. Also, be sure to mention allergies you have to medications.

What happens during colonoscopy?

Colonoscopy is well-tolerated and rarely causes much pain. You might feel pressure, bloating or cramping during the procedure. Typically, your doctor will give you a sedative or painkiller to help you relax and better tolerate any discomfort. You will lie on your side or back while your doctor slowly advances a colonoscope along your large intestine to examine the lining. Your doctor will examine the lining again as he or she slowly withdraws the colonoscope. The procedure itself usually takes less than 45 minutes, although you should plan on two to three hours for waiting, preparation and recovery. In some cases, the doctor cannot pass the colonoscope through the entire colon to where it meets the small intestine. Your doctor will advise you whether any additional testing is necessary.

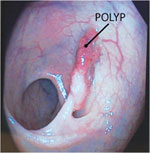

What if the colonoscopy shows something abnormal?

If your doctor thinks an area needs further evaluation, he or she might pass an instrument through the colonoscope to obtain a biopsy (a small sample of the colon lining) to be analyzed. Biopsies are used to identify many conditions, and your doctor will often take a biopsy even if he or she doesn’t suspect cancer. If colonoscopy is being performed to identify sites of bleeding, your doctor might control the bleeding through the colonoscope by injecting medications or by cauterization (sealing off bleeding vessels with heat treatment) or by use of small clips. Your doctor might also find polyps during colonoscopy, and he or she will most likely remove them during the examination. These procedures don’t usually cause any pain.

What are polyps and why are they removed?

Polyps are abnormal growths in the colon lining that are usually benign (noncancerous). They vary in size from a tiny dot to several inches. Your doctor can’t always tell a benign polyp from a malignant (cancerous) polyp by its outer appearance, so he or she will usually remove polyps for analysis. Because cancer begins in polyps, removing them is an important means of preventing colorectal cancer.

How are polyps removed?

Your doctor may destroy tiny polyps by fulguration (burning) or by removing them with wire loops called snares or with biopsy instruments. Your doctor will use a technique called “snare polypectomy” to remove larger polyps. Your doctor will pass a wire loop through the colonoscope and remove the polyp from the intestinal wall using an electrical current. You should feel no pain during the polypectomy.

What happens after a colonoscopy?

You will be monitored until most of the effects of the sedatives have worn off. You might have some cramping or bloating because of the air introduced into the colon during the examination. This should disappear quickly when you pass gas. Your physician will explain the results of the examination to you, although you’ll probably have to wait for the results of any biopsies performed. If you have been given sedatives during the procedure, someone must drive you home and stay with you. Even if you feel alert after the procedure, your judgment and reflexes could be impaired for the rest of the day. You should be able to eat after the examination, but your doctor might restrict your diet and activities, especially after polypectomy. Your doctor will advise you on this.

What are the possible complications of colonoscopy?

Colonoscopy and polypectomy are generally safe when performed by doctors who have been specially trained and are experienced in these procedures. One possible complication is a perforation, or tear, through the bowel wall that could require surgery. Bleeding might occur at the site of biopsy or polypectomy, but it’s usually minor. Bleeding can stop on its own or be controlled through the colonoscope; it rarely requires follow-up treatment. Some patients might have a reaction to the sedatives or complications from heart or lung disease. Although complications after colonoscopy are uncommon, it’s important to recognize early signs of possible complications. Contact your doctor if you notice severe abdominal pain, fever and chills, or rectal bleeding. Note that bleeding can occur several days after the procedure.

What is flexible sigmoidoscopy?

Flexible sigmoidoscopy lets your doctor examine the lining of the rectum and a portion of the colon (large intestine) by inserting a flexible tube about the thickness of your finger into the anus and slowly advancing it into the rectum and lower part of the colon.

What preparation is required?

Your doctor will tell you what cleansing routine to use. In general, preparation consists of one or two enemas prior to the procedure but could include laxatives or dietary modifications as well. However, in some circumstances your doctor might advise you to forgo any special preparation. Because the rectum and lower colon must be completely empty for the procedure to be accurate, it is important to follow your doctor’s instructions carefully.

Should I continue my current medications?

Most medications can be continued as usual. Inform your doctor about medications that you’re taking, particularly aspirin products, anti-coagulants (blood thinners such as warfarin or heparin), or clopidogrel, as well as any allergies you have to medications.

What can I expect during flexible sigmoidoscopy?

Flexible sigmoidoscopy is usually well-tolerated. You might experience a feeling of pressure, bloating or cramping during the procedure. You will lie on your side while your doctor advances the sigmoidoscope through the rectum and lower part of the colon. As your doctor withdraws the instrument, your doctor will carefully examine the lining of the intestine.

What if the flexible sigmoidoscopy finds something abnormal?

If your doctor sees an area that needs further evaluation, he or she might take a biopsy (tissue sample) to be analyzed. Obtaining a biopsy does not cause pain or discomfort. Biopsies are used to identify many conditions, and your doctor might order one even if he or she doesn’t suspect cancer. If your doctor finds polyps, he or she might take a biopsy of them as well. Polyps, which are growths from the lining of the colon, vary in size and types. Polyps known as “hyperplastic” might not require removal, but other benign polyps known as “adenomas” have a small risk of becoming cancerous. Your doctor will likely ask you to have a colonoscopy (a complete examination of the colon) to remove any large polyps or any small adenomas.

What happens after a flexible sigmoidoscopy?

Your doctor will explain the results to you when the procedure is done. You might feel bloating or some mild cramping because of the air that was passed into the colon during the examination. This will disappear quickly when you pass gas. You should be able to eat and resume your normal activities after leaving your doctor’s office or the hospital, assuming you did not receive any sedative medication.

What are possible complications of flexible sigmoidoscopy?

Flexible sigmoidoscopy and biopsy are safe when performed by doctors who are specially trained and experienced in these endoscopic procedures. Complications are rare, but it’s important for you to recognize early signs of possible complications. Contact your doctor if you notice severe abdominal pain, fevers and chills, or rectal bleeding. Note that rectal bleeding can occur several days after the exam.

What is a colon polyp?

Polyps are benign growths (noncancerous tumors or neoplasms) involving the lining of the bowel. They can occur in several locations in the gastrointestinal tract but are most common in the colon. They vary in size from less than a quarter of an inch to several inches in diameter. They look like small bumps growing from the lining of the bowel and protruding into the lumen (bowel cavity). They sometimes grow on a “stalk” and look like mushrooms. Some polyps can also be flat. Many patients have several polyps scattered in different parts of the colon. Some polyps can contain small areas of cancer, although the vast majority of polyps do not.

How common are colon polyps? What causes them?

Polyps are very common in adults, who have an increased chance of acquiring them, especially as we get older. While quite rare in 20-year-olds, it’s estimated that the average 60-year-old without special risk factors for polyps has a 25 percent chance of having a polyp. We don’t know what causes polyps. Some experts believe a high-fat, low-fiber diet can be a predisposition to polyp formation. There may be a genetic risk to develop polyps as well.

What are known risks for developing polyps?

The biggest risk factor for developing polyps is being older than 50. A family history of colon polyps or colon cancer increases the risk of polyps. Also, patients with a personal history of polyps or colon cancer are at risk of developing new polyps. In addition, there are some rare polyp or cancer syndromes that run in families and increase the risk of polyps occurring at younger ages.

Are there different types of polyps?

There are two common types: hyperplastic polyp and adenoma. The hyperplastic polyp is typically not at risk for cancer. The adenoma, however, is thought to be the precursor (origin) for almost all colon cancers, although most adenomas never become cancers. Histology (examination of tissue under a microscope) is the best way to differentiate between hyperplastic and adenomatous polyps. Although it’s impossible to tell which adenomatous polyps will become cancers, larger polyps are more likely to become cancers and some of the largest ones (those larger than 1 inch) can already contain small areas of cancer. Because your doctor cannot usually be certain of the tissue type by the polyp’s appearance, doctors generally recommend removing all polyps found during a colonoscopy.

How are polyps found?

Most polyps cause no symptoms. Larger ones can cause blood in the stool, but even they are usually asymptomatic. Therefore, the best way to detect polyps is by screening individuals with no symptoms. Several other screening techniques are available: testing stool specimens for traces of blood, performing sigmoidoscopy to look into the lower third of the colon or using a radiology test such as a barium enema or CT colonography.

If one of these tests finds or suspects polyps, your doctor will generally recommend colonoscopy to remove them. Because colonoscopy is the most accurate way to detect polyps, many experts now recommend colonoscopy as a screening method so that any polyps found or suspected can be removed during the same procedure.

How are polyps removed?

Most polyps found during colonoscopy can be completely removed during the procedure. Various removal techniques are available; most involve removing them with a wire loop, biopsy forceps and/or burning the polyp base with an electric current. This is called polyp resection. Because the bowel’s lining isn’t sensitive to cutting or burning, polyp resection doesn’t cause discomfort. Resected polyps are then examined under a microscope by a pathologist to determine the tissue type and to detect any cancer. If a large or unusual looking polyp is removed or left for possible surgical management, the endoscopist may mark the site by injecting small amounts of sterile India ink or carbon black into the bowel wall. This is called endoscopic tattooing.

What are the risks of polyp removal?

Polyp removal (or polypectomy) during colonoscopy is a routine outpatient procedure. Possible complications, which are uncommon, include bleeding from the polypectomy site and perforation (a hole or tear) of the colon. Bleeding from the polypectomy site can be immediate or delayed for several days; persistent bleeding can almost always be stopped by treatment during another colonoscopy.Perforations rarely occur and may require surgery to repair.

How often do I need colonoscopy if I have polyps removed?

Your doctor will decide when your next colonoscopy is necessary. The timing depends on several factors, including the number and size of polyps removed, the polyps’ tissue type and the quality of the colon cleansing for your previous procedure. The quality of cleansing affects your doctor’s ability to see the surface of the colon. If the polyps were small and the entire colon was well seen during your colonoscopy, doctors generally recommend a repeat colonoscopy in three to five years. If your repeat colonoscopy doesn’t show any indication of polyps, you might not need another procedure for an additional five years. However, if the polyps were large and flat, your doctor might recommend an interval of only months before a repeat colonoscopy to assure complete polyp removal. Your doctor will discuss those options with you.

What is Esophageal Dilation?

Esophageal dilation is a procedure that allows your doctor to dilate, or stretch, a narrowed area of your esophagus [swallowing tube]. Doctors can use various techniques for this procedure. Your doctor might perform the procedure as part of a sedated endoscopy. Alternatively, your doctor might apply a local anesthetic spray to the back of your throat and then pass a weighted dilator through your mouth and into your esophagus.

Why is esophageal dilation done?

The most common cause of narrowing of the esophagus, or stricture, is scarring of the esophagus from reflux of stomach acid occurring in patients with heartburn. Patients with a narrowed portion of the esophagus often have trouble swallowing; food feels like it is “stuck” in the chest region, causing discomfort or pain. Less common causes of esophageal narrowing are webs or rings (which are thin layers of excess tissue), cancer of the esophagus, scarring after radiation treatment or a disorder of the way the esophagus moves [motility disorder].

How should I prepare for the procedure?

An empty stomach allows for the best and safest examination, so you should have nothing to drink, including water, for at least six hours before the examination. Your doctor will tell you when to start fasting. Tell your doctor in advance about any medications you take, particularly aspirin products or anticoagulants (blood thinners such as warfarin or heparin), or clopidogrel. Most medications can be continued as usual, but you might need to adjust your usual dose before the examination. Your doctor will give you specific guidance. Tell your doctor if you have any allergies to medications as well as medical conditions such as heart or lung disease. Also, tell your doctor if you require antibiotics prior to dental procedures, because you might need antibiotics prior to esophageal dilation as well.

What can I expect during esophageal dilation?

Your doctor might perform esophageal dilation with sedation along with an upper endoscopy. Your doctor may spray your throat with a local anesthetic spray, and then give you sedatives to help you relax. Your doctor then will pass the endoscope through your mouth and into the esophagus, stomach and duodenum. The endoscope does not interfere with your breathing. At this point your doctor will determine whether to use a dilating balloon or plastic dilators over a guiding wire to stretch your esophagus. You might experience mild pressure in the back of your throat or in your chest during the procedure. Alternatively, your doctor might start by spraying your throat with a local anesthetic. Your doctor will then pass a tapered dilating instrument through your mouth and guide it into the esophagus. Your doctor may also use x-rays during the esophageal dilation procedure.

What can I expect after esophageal dilation?

After the dilation is done, you will probably be observed for a short period of time and then allowed to return to your normal activities. You may resume drinking when the anesthetic no longer causes numbness to your throat, unless your doctor instructs you otherwise. Most patients experience no symptoms after this procedure and can resume eating the next day, but you might experience a mild sore throat for the remainder of the day. Your doctor will advise you on eating and drinking. If you received sedatives, you probably will be monitored in a recovery area until you are ready to leave. You will not be allowed to drive after the procedure even though you might not feel tired. You should arrange for someone to accompany you home, because the sedatives might affect your judgment and reflexes for the rest of the day.

What are the potential complications of esophageal dilation?

Although complications can occur even when the procedure is performed correctly, they are rare when performed by doctors who are specially trained. A perforation, or a hole of the esophagus lining, occurs in a small percentage of cases and may require surgery. A tear of the esophagus lining may occur and bleeding may result. There are also possible risks of side effects from sedatives. It is important to recognize early signs of possible complications. If you have chest pain, fever, trouble breathing, difficulty swallowing, bleeding or black bowel movements after the test, tell your doctor immediately.

Will repeat dilations be necessary?

Depending on the degree and cause of narrowing of your esophagus, it is common to require repeat dilations. This allows the dilation to be performed gradually and decreases the risk of complications. Once the stricture, or narrowed esophagus, is completely dilated, repeat dilations may not be required. If the stricture was due to acid reflux, acid-suppressing medicines can decrease the risk of stricture recurrence. Your doctor will advise you on this.

What is capsule endoscopy?

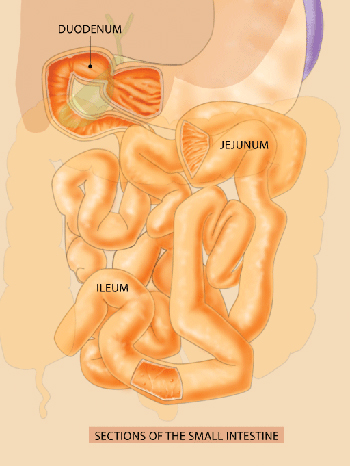

Capsule Endoscopy lets your doctor examine the lining of the middle part of your gastrointestinal tract, which includes the three portions of the small intestine (duodenum, jejunum and ileum). Your doctor will give you a pill-sized video camera for you to swallow. This camera has its own light source and takes pictures of your small intestine as it passes through. These pictures are sent to a small recording device you wear on your body. Your doctor will be able to view these pictures at a later time and might be able to provide you with useful information regarding your small intestine.

Why is capsule endoscopy done?

Capsule endoscopy helps your doctor evaluate the small intestine. This part of the bowel cannot be reached by traditional upper endoscopy or by colonoscopy. The most common reason for doing capsule endoscopy is to search for a cause of bleeding from the small intestine. It may also be useful for detecting polyps, inflammatory bowel disease (Crohn’s disease), ulcers and tumors of the small intestine. As is the case with most new diagnostic procedures, not all insurance companies are currently reimbursing for this procedure. You may need to check with your own insurance company to ensure that this is a covered benefit.

How should I prepare for the procedure?

An empty stomach allows for the best and safest examination, so you should have nothing to eat or drink, including water, for approximately twelve hours before the examination. Your doctor will tell you when to start fasting. Tell your doctor in advance about any medications you take including iron, aspirin, bismuth subsalicylate products and other over-the-counter medications. You might need to adjust your usual dose prior to the examination. Discuss any allergies to medications as well as medical conditions, such as swallowing disorders and heart or lung disease. Tell your doctor of the presence of a pacemaker or defibrillator, previous abdominal surgery, or previous history of bowel obstructions, inflammatory bowel disease or adhesions. Your doctor may ask you to do a bowel prep/cleansing prior to the examination.

The small intestine can be the site of several gastrointestinal disorders, including bleeding, polyps, inflammatory bowel disease, ulcers, and tumors. Capsule endoscopy allows for examination of the small intestine, which cannot be easily reached by traditional methods of endoscopy.

What can I expect during capsule endoscopy?

Your doctor will prepare you for the examination by applying a sensor device to your abdomen with adhesive sleeves (similar to tape). The pill-sized capsule endoscope is swallowed and passes naturally through your digestive tract while transmitting video images to a data recorder worn on your belt for approximately eight hours. At the end of the procedure you will return to the office and the data recorder is removed so that images of your small bowel can be put on a computer screen for physician review.

Most patients consider the test comfortable. The capsule endoscope is about the size of a large pill. After ingesting the capsule and until it is excreted, you should not be near an MRI device or schedule an MRI examination.

What happens after capsule endoscopy?

You will be able to drink clear liquids after two hours and eat a light meal after four hours following the capsule ingestion, unless your doctor instructs you otherwise. You will have to avoid vigorous physical activity such as running or jumping during the study.

Your doctor generally can tell you the test results within the week following the procedure; however, the results of some tests might take longer.

What are the possible complications of capsule endoscopy?

Although complications can occur, they are generally rare when doctors who are specially trained and experienced in this procedure perform the test. There is a potential for the capsule to be stuck at a narrowed spot in the digestive tract resulting in bowel obstruction. This usually relates to a stricture (narrowing) of the digestive tract from inflammation, prior surgery or tumor. It is important to recognize obstruction early. Signs of obstruction include unusual bloating, abdominal pain, nausea or vomiting. You should call your doctor immediately for any such concerns. Also, if you develop a fever after the test, have trouble swallowing or experience chest pain, tell your doctor immediately. Be careful not to prematurely disconnect the system as this may result in loss of pictures being sent to your recording device.

The Benefits of Endoscopy

Endoscopy involves the use of flexible tubes, known as endoscopes, to provide a close-up, color television view of the inside of the digestive tract. Upper endoscopes are passed through the mouth to visualize the esophagus (food pipe), stomach, and duodenum (first portion of the small intestine), while lower endoscopes (colonoscopes) are passed through the rectum to view the colon or large intestine. Other special endoscopes allow physicians to view portions of the pancreas, liver and gallbladder as well.

Endoscopy has been a major advance in the treatment of gastrointestinal diseases. For example, the use of endoscopes allows the detection of ulcers, cancers, polyps and

sites of internal bleeding. Through endoscopy, tissue samples (biopsies) may be obtained, areas of blockage can be opened, and active bleeding can be stopped. Polyps in the colon can be removed, which has been shown to prevent colon cancer.

Endoscopy is easily carried out on an outpatient basis and is very well tolerated by patients. The technique of endoscopy is extremely safe, with very low rates of complications, when performed by a properly trained endoscopist, such as members of the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE).

The Characteristics of an Endoscope

An endoscope consists of a flexible tube, which is passed into the digestive tract to provide a video image, and a control section, which allows the endoscopist to maneuver the tip of the flexible tube in a precise manner. Within the tube are the electronics necessary to obtain the video image, cables that allow control of the flexible tip, and channels that permit the passage of devices to sample tissue, stop bleeding, or remove polyps. The endoscope is a complex but durable instrument and is safe for use in thousands of procedures.

Effectiveness of the Reprocessing Guidelines

The dissemination and implementation of the guidelines for endoscope reprocessing (cleaning and disinfecting) outlined here have resulted in a remarkable safety record for endoscopy. Based on medical literature, the Technology Committee of the ASGE estimates that the chance that a serious infection could be transmitted by endoscopy is only about 1 in 1.8 million. Given the multiple benefits of endoscopy, it is no wonder that the number of procedures performed grows each year and that endoscopy is a mainstay of digestive disease treatment plans and health maintenance strategies. Endoscope manufacturers are continually improving the design of endoscopes to ensure patient safety.

Quality Assurance and Training

Any facility in which gastrointestinal endoscopy is performed must have an effective quality assurance program in place to ensure that endoscopes are reprocessed properly. Quality assurance programs for endoscopy must include the supervision, training, and annual competency review of all staff involved in the process, systems that assure availability of appropriate equipment and supplies at all times, and strict procedures for reporting possible problems.

Availability of Reprocessing Guidelines

The ASGE guidelines for infection control during gastrointestinal endoscopy provide the latest techniques and step-by-step directions on the proper procedure for cleaning and disinfecting endoscopes. These are distributed to all members of ASGE and are regularly reviewed and updated. They are also easily accessed on the ASGE Web site (www.asge.org) or by calling or writing ASGE.

An endoscope is a medical device containing a flexible tube, a light, and a camera. It is used by expert physicians to look inside the digestive tract. Endoscopy allows the physician to examine the lining of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, which includes the esophagus, stomach, duodenum, colon, and rectum. The physician controls the movement of the flexible tube using the endoscope handle.

How the Preparation of an Endoscope for Each Procedure Ensures Patient Safety

In all areas of medicine and surgery, complex medical devices are generally not discarded after use in one patient but rather are reused in subsequent patients.

This practice is very safe, provided that the devices are properly prepared, or reprocessed, prior to each procedure, so as to eliminate any risk that an infection could be transmitted from one patient to another.

Prior to the performance of a procedure, an endoscope must be carefully cleaned and disinfected according to guidelines published by the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy, which have been endorsed by every major medical association dealing with endoscopy and infection control. The steps involved in cleaning and disinfecting an endoscope are as follows:

Mechanical cleaning. The operating channels and external portions of the endoscope are washed thoroughly, wiped with special liquids that contain enzymes, and brushed with special cleaning instruments. Studies have shown that these steps alone can eliminate potentially harmful viruses and other microbes from an endoscope. However, much more is done before the endoscope is considered ready for use.

Leakage testing. The endoscope is tested to be sure that there are no leaks in its internal operating channels. This not only ensures peak performance of the endoscope, but also allows immediate detection of internal defects that could be a potential focus of infection within the device. Despite its complex electronics, an entire endoscope can be submersed completely in liquid so that leakage testing can be carried out.

Use of chemical disinfectants. Next, the endoscope is soaked continuously for an appropriate time period with one of several approved liquid chemicals that destroy microorganisms which can cause infections in humans, including the AIDS virus, hepatitis viruses, and potentially harmful bacteria. There are a variety of chemical disinfectants used to achieve high-level disinfection. This process eliminates virtually all microbial life except for some inactivate dormant organisms known as spores. However, spores are uncommonly found in endoscopes and, even if present, are not harmful to humans. Although most high-level disinfectants are also sterilants (which kills all spores), this requires a much longer exposure time, and has not been shown to be necessary.The human mouth, small intestine, colon and rectum contain millions of non-harmful bacteria. Therefore, as soon as the endoscope touches the internal surface of a patient, it is not sterile. The goal of a “sterile” endoscope from the beginning to the end of a procedure is not achievable. Therefore, the goal of reprocessing is to eliminate from the endoscope any potentially harmful microbes. This goal can be achieved with high-level disinfectant chemicals and by following standard reprocessing guidelines.

Rinsing and drying. After exposure to the chemical disinfectant, the endoscope channels are flushed with sterile water followed by alcohol and then air dried to eliminate any moisture that could be a site of bacterial growth from the environment. The endoscope is then stored on a specialized hanger to keep it dry and free of contamination.

What is diverticulosis?

Diverticulosis is a condition in which there are small pouches or pockets in the wall or lining of any portion of the digestive tract. These pockets occur when the inner layer of the digestive tract pushes through weak spots in the outer layer. A single pouch is called a diverticulum. The pouches associated with diverticulosis are most often located in the lower part of the large intestine (the colon). Some people may have only several small pouches on the left side of the colon, while others may have involvement in most of the colon.

Who gets diverticulosis?

Diverticulosis is a common condition in the United States that affects half of all people over 60 years of age and nearly everyone by the age of 80. As a person gets older, the pouches in the digestive tract become more prominent. Diverticulosis is unusual in people under 40 years of age. In addition, it is uncommon in certain parts of the world, such as Asia and Africa.

What causes diverticulosis?

Because diverticulosis is uncommon in regions of the world where diets are high in fiber and rich in grains, fruits and vegetables, most doctors believe this condition is due in part to a diet low in fiber. A low-fiber diet leads to constipation, which increases pressure within the digestive tract with straining during bowel movements. The combination of pressure and straining over many years likely leads to diverticulosis.

The easiest way to increase fiber intake is to eat more fruits, vegetables and grains. Diverticulosis is uncommon in regions of the world where diets are high in fiber and rich in grains, fruits and vegetables. Most doctors believe this condition is due in part to a diet low in fiber.

What are the symptoms of diverticulosis?

Most people who have diverticulosis are unaware that they have the condition because it usually does not cause symptoms. It is possible that some people with diverticulosis experience bloating, abdominal cramps or constipation due to difficulty in stool passage through the affected region of the colon.

How is the diagnosis of diverticulosis made?

Because most people do not have symptoms, diverticulosis is often found incidentally during evaluation for another condition or during a screening exam for polyps. Gastroenterologists can directly visualize the diverticula (more than one pouch, or diverticulum) in the colon during a procedure that uses a small camera attached to a lighted, flexible tube inserted through the rectum. One of these procedures is a sigmoidoscopy, which uses a short tube to examine only the rectum and lower part of the colon. A colonoscopy uses a longer tube to examine the entire colon. Diverticulosis can also be seen using other imaging tests, for example by computed tomography (CT) scan or barium x-ray.

What is the treatment for diverticulosis?

Once diverticula form, they do not disappear by themselves. Fortunately, most patients with diverticulosis do not have symptoms and, therefore, do not need treatment.

When diverticulosis is accompanied by abdominal pain, bloating or constipation, your doctor may recommend a high-fiber diet to help make stools softer and easier to pass. While it is recommended that we consume 20 to 35 grams of fiber daily, most people only get about half that amount. The easiest way to increase fiber intake is to eat more fruits, vegetables and grains. Apples, pears, broccoli, carrots, squash, baked beans, kidney beans, and lima beans are a few examples of high-fiber foods. As an alternative, your doctor may recommend a supplemental fiber product such as psyllium, methylcellulose, or poly-carbophil. These products come in various forms including pills, powders and wafers. Supplemental fiber products help to bulk up and soften the stool, which makes bowel movements easier to pass. Your doctor may also prescribe medications to help relax spasms in the colon that cause abdominal cramping or discomfort.

Bleeding in the colon may occur from a diverticulum. Intestinal blockage may occur in the colon from repeated attacks of diverticulitis. If left untreated, diverticulitis may lead to an abscess outside the colon wall or an infection in the lining of the abdominal cavity.

Are there complications from diverticulosis?

Diverticulosis may lead to several complications including inflammation, infection, bleeding or intestinal blockage. Fortunately, diverticulosis does not lead to cancer.

Diverticulitis occurs when the pouches become infected or inflamed. This condition usually produces localized abdominal pain, tenderness to touch and fever. A person with diverticulitis may also experience nausea, vomiting, shaking, chills or constipation. Your doctor may order a CT scan to confirm a diagnosis of diverticulitis. Minor cases of infection are usually treated with oral antibiotics and do not require admission to the hospital. If left untreated, diverticulitis may lead to a collection of pus (called an abscess) outside the colon wall or a generalized infection in the lining of the abdominal cavity, a condition referred to as peritonitis. Usually a CT scan is required to diagnose an abscess, and treatment usually requires a hospital stay, antibiotics administered through a vein and possibly drainage of the abscess. Repeated attacks of diverticulitis may require surgery to remove the affected portion of the colon. Bleeding in the colon may occur from a diverticulum and is called diverticular bleeding. This is the most common cause of major colonic bleeding in patients over 40 years old and is usually noticed as passage of red or maroon blood through the rectum. Most diverticular bleeding stops on its own; however, if it does not, a colonoscopy may be required for evaluation. If bleeding is severe or persists, a hospital stay is usually required to administer intravenous fluids or possibly blood transfusions. In addition, a colonoscopy may be required to determine the cause of bleeding and to treat the bleeding. Occasionally, surgery or other procedures may be necessary to stop bleeding that cannot be stopped by other methods. Intestinal blockage may occur in the colon from repeated attacks of diverticulitis. In this case, surgery may be necessary to remove the involved area of the colon.